The Stability of the Urban Ecology

Increasing mobility by application of technology has been a major theme in American history. It is associated with the consumption of the space that seemed so abundant when “discovered” by the European invasion after 1492. The phrase “limits to mobility” could only imply a challenge to overcome constraints. That is the narrative picturesquely presented by a collection of articles starting in 1944 by “The Old Roadbuilder” in American Highways, the mouthpiece of the American Association of Highway Officials (AASHO). The author was Albert Rose, an employee of the Bureau of Public Roads with artwork by Carl Rakeman [collected in Albert C. Rose, Historic American Roads: From Frontier Trails to Superhighways, Crown Publishers, Inc., 1976]. I saw much of the artwork hanging in the halls of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) even in the 1990s. The artwork and its image of history also became a core of the FHWA’s history [America’s Highways, 1976].

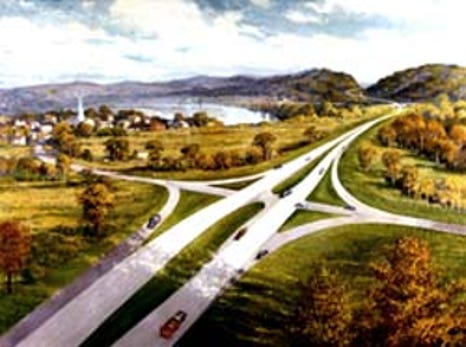

Rakeman’s illustrations not only trace the progress of mobility but the “progress” from settling the land to exploiting what was settled:

Carl Rakeman, 1809—The Natchez Trace [FHWA]

Carl Rakeman, 1945—A Rural Interstate Highway [FHWA]

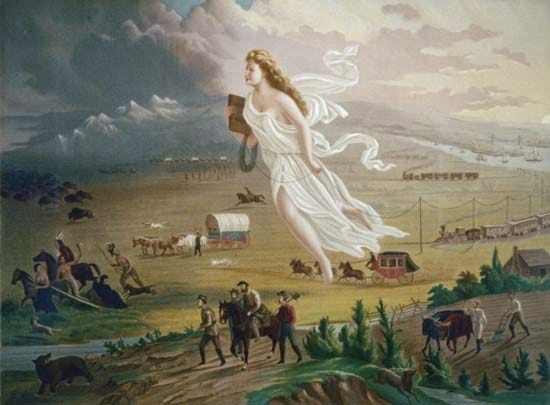

The crusade to overcome limits to mobility played out in the constitutional debate about internal improvements [e.g., John Lauritz Larson, Internal Improvement: National public works and the promise of popular government in the early United States, 2001]. The national State pursued the conquest of our continental space extra-constitutionally. It sent forth the Army to acquire the spatial territory that constitutes a State exemplifying eminent-domain power as defined by Grotius [The Law of War and Peace, 1625]. The power of a State to exist is inherent and to exist it must have space. Eminent domain also became manifest destiny, the conjunction of European superiority and the particular bounds of American-continental topography.

American Progress, chromolithograph print, George A. Crofutt, 1873

The problem arises when the space develops as the “destiny” of that very civilization. That development is not a wavefront of spatial expansion but rather the interaction of distributed agents in the complex form of access. Rules of how to interact matter and so does where the interactors are located. We have legal and economic governance for which the aboriginal ecology was eliminated. Owning property, especially space, is a primary principle to preserve the distributed right of its development. It is a principle that conflicts with how the ecology is organized and its agents, beside us, interact.

We developed the urban-industrial ecology on the space we got. That means our social interactions dominate what we get and give and so how we locate relative to who or what gets and gives. Our urban access form is just what occurs in that case. Access is a spatial potential measured by relative locations and the efficiency (perhaps a cost) of connecting the locations.

For a long time in our history the access form was taken for granted and myopically viewed from the individual perspective of “here is a good place to locate”. The principle of agglomeration—that a good place is close to where other people and markets are—dominated the mere frontier transient of arriving at the edge of this urban-access form. The settler surveyed his land and then immediately got down to how to make money out of it. The myth of the “Frontier in American History” [Frederick Jackson Turner, the primary essay being from 1893, called “The Significance of the Frontier in American History”] is about the transient edge of getting space, not a stable form of development. That is what people left back in “old Europe”. And yet that form is just what we replicated in the new space we obtained. That last thing wanted was for that form to be perturbed. It was to be defended against any others wanting the space. Eventually we turned against the immigrants who we once were. And with that a problem of mobility occurs, of how easy it is to to get from one place to another. It becomes a matter of formal stability. It becomes NIMBYism but also the tragedy of projects, by the State, for mobility that demolished so much of our urban development.

The Efficiency of Consuming Space

This work on Limits to Mobility (LTM) [the one-volume version here] turns around the challenge of consuming space to the limits that are necessary to preserve the access form. There is a difference between mobility as an efficiency of consuming space and its role of connection in a stable access form. The difference had to be recognized as we developed the space we got. That is why the “closing of the frontier” that Turner enunciated in 1893 is more important than the myth that survives from there being a frontier. It was the critical point on what we would do with mobility and its technologies. It is when the limits had to be adhered to as much as any formal laws of behavior.

This basic idea in LTM has been treated in previous posts and primarily by the example of how we lost the transit-oriented development (TOD) form of our urban ecology and got trapped in the ongoing transient of auto-oriented sprawl (AOS). The decay of central places only exacerbates the desire for the efficiency of getting a “different” space as the edge of “old” development becomes the new frontier, the crabgrass frontier [and a book by Kenneth T. Jackson, 1985]. The transient is the absurd dilemma of trying to escape “the congestion that followed us out here”. Its other version is complaining about the highway congestion we are in, because we are in it. These are cases of the Tragedy of the Commons (TOTC) that just illustrate the divergence between individual and collective or formal efficiency.

Sometime around 1893 we should have had the sense to recognize the difference between efficiency in consuming space and the role of mobility in the stability of the access form. Instead we got State policy to promote mobility for the consumption of urban space by what became its dominant technology: The automobile.

The Stability of Form

The basis of LTM is the dynamics of self-organizing systems, of which our urban ecology is a familiar example. There is a reason that is alien to “transport planning” and so unexpected by anyone wanting to read about mobility.

By now it is accepted by many that access should be the criterion of policy. I do not say “transport planning” because we do not have that. Instead we have the programming and engineering of modal projects, exactly what the so-called Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) are for. My historical view of MPOs is in LTM Part II and of their technical function in LTM Part III. But no one does “metropolitan planning”. Because of the AOS our conurbations just expand and have no stable access form. All locations are at risk and access is inequitable according to the ability to buy efficient mobility. There was never no risk and no inequity, but the AOS has just let auto-mobility exacerbate both.

The stability of form, that any transient will have a mature form of development, is a topic in system engineering and implicitly in ecology. We can view the ecology (the form we live in, along with all other genomes) in the same way as any space: Consume it or participate in a stable access form. The urban form is just more familiar and relevant to most of us.

There has been much research on the stability of ecologies in the sense of species populations and their modes of interaction (predation, competition and mutualism). The matrices of species interaction do not include specific access forms or who is doing what where. That is just aggregated, statistically, to the formal level and population numbers. Our urban equivalent for our one species is GDP, a dollar measure that aggregates all that is otherwise incommensurate as attributes of our lives let alone the rest of the ecology. Access being a spatially distributed measure (a scalar field) is just beyond the simple uni-measure of dollar transactions and the stocks that are available for transaction in any accounting period.

GDP is about the transient of growth and it drives (sic) an indifference to the transience of access form. We get stuck in a quibble about whether some urban form is actually more productive or just assume that more mobility means more productivity. The latter assumption is traceable to Adam Smith [The Wealth of Nations, 1776. Book I, Ch. XI, Part I] who made a scale economy argument for factories (in some place) when their hinterland market could be extended by the mobility of “Good roads, canals and navigable rivers, by diminishing the expence of carriage…” Smith was taken almost verbatim by Hamilton [Report on Manufactures, final version 1791, Syrett edition, pp. 310-311] as:

XI. The facilitating of the transportation of commodities.

Improvements favoring this object intimately concern all the domestic interests of a community; but they may, without impropriety, be mentioned as having, an important relation to manufactures. There is, perhaps, scarcely any thing which has been better calculated to assist the manufacturers of Great Britain, than the melioration of the public roads of that kingdom, and the great progress which has been of late made in opening canals. Of the former, the United States stand much in need; for the latter, they present uncommon facilities.

Despite Hamilton we have, for the same reasons, no serious industrial policy nor urban development policy. That “just happens”. What survives is the idea that the State can, and should undertake (internal) “improvements” that just “concern all domestic interests”. And there is nothing more pervasive, and indifferent to what goes where, than mobility.

The flaw in Smith, Hamilton and ever since is that the analysis of mobility is as partial and incomplete as its role in access. Smith imagined an indefinitely growing factory (necessarily placed in an urban center) whose market also stayed in place and would be reached by tentacles of mobility. The same mobility would however change the access form and where things were. As we now find, with mobility all form changes, the factories move with the frontier and eventually across the Pacific. We get Trump echoing Hamilton, but tariffs were only one part of Hamilton’s scheme and one of the most polarizing in the growing North-South sectionalism.

Mobility and Accountability

I started LTM by focusing on the unsettling effects of mobility on urban form. Over my career in systems engineering logical interaction (the “Internet”) dominated physical interaction. Computer-mediated information and decisions is what my career was concerned with. LTM tries to give equal consideration to bandwidth as the measure of information consumption as mobility is of space. The case can be made, and is increasingly evident, that mobility and bandwidth are the parameters of social instability in access and (ideo-)logical form.

The basic factor however is accountability to each other, to ecological risk and equity. When we are distant in space we do not care. When we have no physical relation to where our messages go we become unaccountable for them. We mirror the unaccountability of State projects to access form.

The ecological-interaction mode of cooperation contrasts with competition or predation. We do have an economic and political hierarchy that adopts competition to get to positions of predation. This is the perversion of ecological self-organization into social Darwinism. The modular community and ruly interaction operates by cooperation and negotiation.

The worst aspects of the TOD followed the competition-predation path. The problems were not going to be solved by the elite moving out of town and demanding parking and highways to return. The automobile is unaccountable to its wayside and where it squats.

The studies of cooperation launched in the era of Axelrod [The Evolution of Cooperation, 1984] arrive at consistent principles: Cooperation comes from accountability to others and that extends to the entire ecology of our “common pool resources” [Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons, 1990]. These issues are featured in LTM Part I. We have to negotiate and be accountable for what we consume. That accountability disappears with the mobility to consume space with indifference to what we pass through or where we leave our automobiles. We encase ourselves in individuality and that is how places and States fall apart.